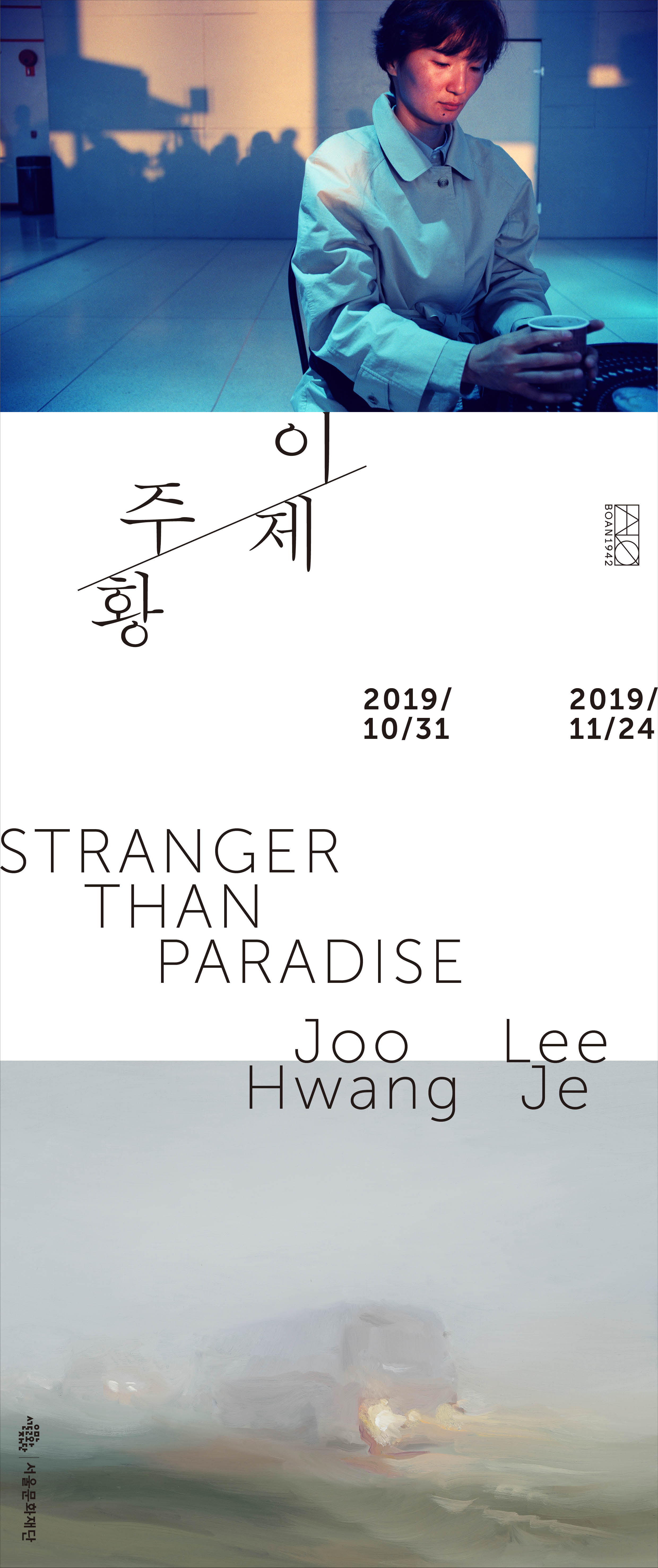

《Stranger than Paradise》 이제·주황 2인전

《Stranger than Paradise》는 그림을 그리는 이제와 사진을 찍는 주황, 두 작가의 2인전입니다. 회화와 사진이라는 매체뿐 아니라, 세대도 배경도 다른 이 두 사람은 서로의 작업을 지지하며 꽤 오랫동안 상대의 매체가 지닌 매혹과 힘에 대해 호기심과 존중 어린 대화를 나눠왔습니다. 이번 전시에서 두 작가는 서로 다른 시기의 기억, 서로 다른 대상으로서 여성의 초상을 이야기합니다. 오늘날 유동하는 존재로서 여성들의 초상, 풍경, 시선이 담긴 이미지로 대화를 나누는 자리에 여러분을 초대합니다.

- 전시일정 _ 2019/10/31 ~ 11/24

- 장소 _ 아트 스페이스 보안 1, 2

- 참여 작가 _ 이제/주황

- 기획 _ 이진실

- 그래픽디자인 _ 볼로로

- 전시촬영_스튜디오 수직수평

- 운영시간: 화~일 12:00~18:00

- 월요일 휴관

- 입장료 무료

*이 전시는 서울문화재단 예술작품지원을 받았습니다.

- October 31–November 24, 2019

- Art Space Boan 1942

- Artists: Joo Hwang, Lee Je

- Curated by Jinshil Lee

전시토크

- 일정: 2019년 11월 16일 토요일 오후 4시

- 장소: 통의동 보안여관 보안클럽 (신관 B2)

- 참여: 백은선 시인, 이진실 기획자, 이제 작가, 주황 작가

- 참가비 무료

- 선착순 입장

Stranger than Paradise

2019/10/31 ~ 11/24

아트스페이스 보안

참여 작가 : 이제/주황

기획 : 이진실

<Stranger than Paradise >는 그림을 그리는 이제와 사진을 찍는 주황, 두 작가의 2인전이다. 회화와 사진이라는 매체뿐 아니라, 세대도 배경도 다른 이 두 사람은 서로의 작업을 지지하며 꽤 오랫동안 상대의 매체가 지닌 매혹과 힘에 대해 호기심과 존중 어린 대화를 나눠왔다. 두 사람의 작업은 여성적 재현 혹은 여성성의 재현이라는 화두나 여성주의 주제의식이 선명하게 드러나는 작업이 아니다. 하지만 두 사람의 작업 모두에 깊숙이 박힌 심지 같은 것이 있다면, 그것은 지금을 살아가는 동시대 여성들의 초상과 풍경, 그리고 정동의 한 끝을 포착하려는 부단한 노력일 것이다.

최근 주황은 소위 ‘K뷰티’라고 불리는 한국 여성들의 정체성과 환상을 작동시키는 기제를 파고드는 <온전한 초상>(2016)시리즈부터 연해주와 일본지역 코리안 디아스포라 여성들의 존재를 주목하는 <민요, 이곳에서 저곳으로>(2018)까지, 여성적 정체성을 형성하는 문화적 간극과 겹겹의 시간성을 간결하게 담아내는 작업을 진행해왔다. 한편, 이제는 2005년 개인전 이래로 주로 사회적·상징적 기호가 각인된 곳이자 부단히 변화하는 유기체로서 여성의 몸 혹은 형상을 캔버스에 그려왔다. 그녀의 그림에서 그러한 여성적 ‘되기’는 소녀의 초상을 비롯해 가슴, 옹기, 열기, 춤, 공동체 등 구상적 형태에 국한되지 않는 리듬이자 역동하는 영토로서 등장해왔다. 이 두 작가의 작업세계에서 여성이라는 화두는 확고한 발언권으로도 자전적 투사로도 기능하지 않는다. 지독한 비행공포증을 가진 주황이 공항에서 처음 만나는 여성들을 찍은 사진들에도, 세월호 이후 소녀들의 초상을 쓸쓸한 바람처럼 담아낸 이제의 그림에서도 여성이라는 형상은 (이 작가들 역시 여성이면서) 아직 말을 걸어보지 못한 바깥의 존재들에 가깝다. 자신의 위치와 서로 다른 경험과 시차에 귀를 기울이는 자의식을 동반한 이들의 작업에서 여성의 초상은 언제나 우리에게 너무나 익숙하면서도 기억해낼 수 없는 얼굴, 혹은 실체라고는 부를 수 없는 복수의 존재처럼 등장한다.

이번 전시에서 두 작가는 서로 다른 시기의 기억, 서로 다른 대상으로서 여성의 초상을 이야기한다. 지난 여름 이제는 두만강을 따라 도문, 훈춘, 우수리스크, 블라디보스토크를 홀로 여행했다. 전혀 ‘우리’와 다르다고 여긴 이들, 혹은 ‘같은’ 민족이라고 여긴 사람들의 삶과 풍경들을 전해 듣는 이야기가 아니라 몸으로 겪고 담아내보자 떠난 길이었다. 주황은 가장 이방인으로 살았던 저 먼 유학시절의 사진들을 꺼냈다. 1996년 이민자, 유색인, 학생, 가난한 예술가들의 일시적 거처가 되었던 이스트빌리지에서 그녀가 만난 이들의 초상, 타자적 응시의 대상이 되었던 ‘우리’의 일상이 담겨있다. 카메라로, 캔버스로 떠낸 이 대상/형상/풍경들에서 일련의 공통분모이자 대화로서 여성적인 것이란 성별정체성에 기반해 민족, 세대, 태생,

계급으로 가름하거나 견주고자 하는 범주가 아니라, 앞길을 알 수 없는 불안한 이들이 시시각각 마주하는 낯섦과 비동일성의 알레고리들이다. 쉽게 규정되지 않고 동질화될 수 없는 존재, 월경(越境)하는 존재, 언제나 떠나는 와중에 있는 존재들의 초상, 풍경, 시선, 그리고 메아리와 같은 응답들이다.

짐 자무시의 로드무비 에서 뉴욕 빈민가에 사는 가난한 두 청춘 윌리와 에디는 어느 날 윌리의 사촌동생 에바를 본다는 구실로 무작정 클리블랜드로 떠난다. 말로만 듣던 클리블랜드에 도착한 에디가 윌리에게 말한다. “웃기지 않아? 새로운 곳에 왔는데 모든 게 다 똑같아.” 그건 매일 집과 일터인 핫도그가게만 오가던 무료한 에바를 ‘납치’해 파라다이스라 불리는 플로리다에 도달했을 때도 마찬가지다. 꿈을 찾아 고향을 탈출한 이방인, 그러나 다시 별볼일 없는 일상의 반경에 갇힌 별볼일 없는 청춘들에게는 그림 같은 경관도, 낙원의 바람도 그저 황량하고 따분할 따름이다. 거기에는 나와 친숙한 그 어떤 곳도 없고, 나를 부르는 그 어떤 이도 없다. 부다페스트에도, 뉴욕, 클리블랜드, 플로리다마저도.

낯선 어딘가로 떠난다는 것은 누구에게는 언제나 설레는 일이고 누구에게는 마지못한 일, 때로는 차마 두려운 일일 것이다. 그것은 단지 떠남을 좋아한다는 취향이나 성정에 따른 것이 아니라, 그 ‘떠나는 처지’를 둘러싼 그/녀 각자의 조건의 불안정성과 친연성의 밀도, 온도에 따른 일이다. 일상의 속박에서 벗어나는 잠깐의 여행과 달리 한 번도 가보지 못한 길을 혼자 떠나는 여정에는 머리끝에서 발끝까지 긴장이 따라붙는다. 다가올 곤란을 무릅쓰고 식구들의 생계를 위해 타국으로 떠나야 하는 이들이나 생존을 위해 필사적으로 바다를 건너야 하는 이들에게 떠남이란 극도의 배타성과 대면하면서 ‘불필요한 타자’로 존재의 추락을 감행해야 하는 일이다. 각자에게 매번 그 강도를 달리하는 이방의 정서, 이 비교 불가능한 안온함과 생경함, 그리고 공포의 감각을 우리가 ‘이주’라고 부르는 시공성으로 명명할 수 있을까? 여하튼 이산, 이주, 여행의 이동성이 자신의 의지보다 삶의 강제로서 수행되는 오늘날, 이 세계의 여성들은 언제나 길을 떠나는 중이며, 어디에서나 이방인이다. 심지어 고향, 그리고 그녀들의 집에서도.

Stranger than Paradise

October 31–November 24, 2019

Art Space Boan 1942

Artists: Joo Hwang, Lee Je

Curated by Jinshil Lee

Stranger than Paradise is a duo show by Joo Hwang, photographer and Lee Je, painter. The two artists differ not only in their artistic media but also in their generation and background, yet have been in close dialogue on the fascination and power of each medium, out of curiosity and respect for each other’s practice. Neither Joo’s work nor Lee’s distinctively emphasize female representation or the representation of femininity; or focus on topics of feminism. However, if one would point out any fundamental core connecting both practices, it would be their ardent endeavor to pursue a possible portraiture, landscape and affect of contemporary women’s life.

In her recent work, Joo Hwang dealt with the cultural discrepancies and layered temporalities that construct female identity through pristine photography. Whereas Liking What You See ( 2016) series investigates the mechanism operating identity and fantasy around South Korean women through the aesthetic of so-called K-Beauty, Minyo, There and Here (2018) highlights the presence of Korean women in diaspora in Primorsky region and Japan. Since her solo exhibition in 2005, Lee Je has been depicting female body or shape as a place imprinted with social and symbolic signs and as ever-transforming organism on her canvas. The female ‘becoming’ in her painting includes portraits of girls, breasts, pottery, heat, dances and communities. Appearing as a rhythm and a dynamic territory, these motifs aren’t confined to their figurative shapes.

In their artistic practices, the female issues unfold neither as a solid urge to speak nor as autobiographical projection. Joo, a serious aerophobe, photographed women she first met in airport, while Lee painted portraits of young girls in solitary wind after the tragedy of Sewol Ferry. In both works, the shapes of women are rather distant beings that they haven’t yet spoken to, even though the artists identify as women themselves. In their works, accompanied by conscious listening to experiences and times that differ from their own, female portraiture always appears as faces that are familiar yet cannot be remembered or as like a multitude that cannot be labeled with any specific identity.

In this exhibition, the two artists unravel their stories about female portraiture as differing memories and objects on each account. During last summer, Lee traveled along the Tumen River by herself, visiting the cities of Tumen, Hunchun, Ussuriysk and Vladivostok. The goal was to physically experience and convey the lives and landscapes of people who were supposed to be totally different from ‘us’ or have been considered to be a part of ‘our’ ethnicity, rather than passively listening to their stories. Joo, on the other hand, reopened her photographs from an older time when she studied in New York, as she felt to have lived ‘most foreign’ in a society. The photographs show portraits of people she met back in 1996 in East Village where it used be temporary base for immigrants, people of color, students and broke artists. These portraits convey the daily life of ‘us,’ subjected to the external gaze as ‘the other.’ In these objects, figures and landscapes framed by means of camera and canvas, the female subject is not a category that divides and competes among ethnicities, generations, origins and class based on gender identities. Instead, it is allegories of unfamiliarity and nonidentity, constantly confronted by people with unstable and uncertain future. They are portraits, landscapes, gazes and echoing responses of people who can be neither easily defined nor identified, of the ones who cross the border and who are always on departure.

In Jim Jarmusch’s road movie Stranger than Paradise, Willie and Eddie, who live in a slum in New York City, decide to leave for Cleveland to visit Eva, Willie’s cousin. Reaching Cleveland for the first time, Eddie says to Willie: “Isn’t it funny? We arrive to a new place but everything is all the same.” That happens again when they ‘kidnap’ bored Eva, who’s been

only commuting between home and the hot dog place where she works. They head to Florida, the so-called paradise. The stranger who escaped home in search for dream yet gets trapped again in mundane everyday. For the mediocre youth, both picturesque scenery and the wind in paradise appear just arid and boring. There, no familiar place and nobody seeking for me exist, neither in Budapest, New York nor in Cleveland and not even in Florida.

To leave for somewhere unknown would be always exciting to someone, inevitable to someone else and even dreadful to others. It won’t simply depend on the taste or the personality fond of leaving, but on the intensity and gravity how instable or affined one is under a circumstance of departure. In contrast to brief trips escaping from the restrictions of daily life, on a solitary journey toward somewhere unknown, tension dominates the traveller from head to toe. For the ones who have to migrate to a foreign country to support the survival of family regardless of approaching hardships or the ones who have to cross the ocean desperately for survival, departure means to confront with extreme xenophobia and to endure the degradation of their existence as ‘the unnecessary other.’ The emotion of the alienation that varies according to each subject, the incomparable tranquility, unfamiliarity and the sense of terror––could these be the time and space of what we call ‘migration’? Anyhow, in our era where the mobility of diaspora, migration and travel is practiced as life necessity than individual motivation, women in the world are always on departure and a stranger everywhere. Even in their own towns and homes.